20 November 2025 Indian Express Editorial

What to Read in Indian Express (Topic and Syllabus wise)

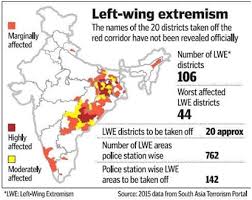

Editorial 1: Decline of Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) in India

Context:

India’s long battle against Left-Wing Extremism appears to be entering its final phase, supported by improved security operations and development-driven governance.

Introduction

Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), popularly associated with the “Red Corridor,” has posed one of India’s most persistent internal security challenges since the 1980s. At its peak (2000–2010), Maoist groups controlled large swathes of tribal and forested regions across Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Maharashtra. The article highlights a major operational success the neutralisation of key Maoist commander Madvi Hidma and reflects on the changing security landscape. Over two decades, coordinated operations, technological support, better policing, and targeted development interventions have gradually reversed Maoists’ influence. Yet, pockets of vulnerability persist, requiring sustained state capacity and community engagement.

Key Issues Discussed in the Editorial

- Historical Evolution of LWE

- Origin traces back to the 1967 Naxalbari uprisingunder Charu Majumdar.

- The People’s War Group (PWG), founded by Kondapalli Seetharamaiah (1980), dominated operations in Andhra Pradesh and adjoining states.

- In 2004, PWG merged with the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) to form CPI (Maoist)—a turning point that consolidated insurgent strength.

- Peak LWE influence created the so-called “Compact Revolutionary Zone”, envisioned as a corridor stretching from Andhra Pradesh to Nepal.

- Why LWE Expanded (1990s–2010)

- Policy incoherence:Frequent shifts between talks and operations, especially in Andhra Pradesh (e.g., 2004 ceasefire), gave Maoists time to regroup.

- Administrative vacuum:Poor presence of civil administration and policing in remote tribal areas.

- Socio-economic grievances:Land alienation, forest rights violations, lack of basic services.

- State capacity gaps:Police shortages, lightly armed forces, inadequate infrastructure.

- Operational Challenges

- Earlier, postings in LWE areas were treated as “punishment”, reducing morale.

- Lack of training, equipment, and intelligencelimited OPS success.

- Gadchiroli police created AC-60 commandos, but larger institutional support was missing.

- Intelligence suffered due to absence of local-language recruits and poor thana networks.

- Turning Point: Strengthened Security Strategy (2014 onwards)

- The editorial notes that a major shift occurred after 2014, when the Centre implemented a structured counter-LWE policy.

- Key Measures (MHA Annual Report 2023–24):

- SAMADHAN doctrine(integrated strategy covering Smart leadership, Aggressive strategy, Motivation, Training, Actionable intelligence, Database, Use of Technology, and No access to financing).

- Security Upgradation Scheme (SUS): Fortified police stations, modern weapons, anti-landmine vehicles.

- Deployment of UAVs/drones, helicopters, and tech-based surveillance.

- Better inter-State coordination, particularly between AP, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Odisha.

- Outcomes:

- LWE-affected districts reduced from 126 (2010)to 38 (2024), now 11 (2025).

- Violent incidents dropped by over 80%from 2010 levels (MHA).

Role of Development & Governance

- The article highlights the Special Central Assistance (SCA)scheme that fills infrastructure gaps in LWE-hit districts.

- Important developmental pillars (MHA, NITI Aayog)

- Road Connectivity Project for LWE Areas (RRP-I & II)

- Better telecom connectivity (Mobile Towers Project)

- Education & health infrastructure

- Implementation of FRA, PESA, MGNREGA

- Banking & digital access

- Skill training & livelihood initiatives

- The combined effect reduced local support for Maoists, weakened recruitment, and improved state legitimacy.

Current Situation: Why Tables Are Turning?

- Elimination of senior leaders.

- Increased surrender ratesamong cadres.

- Erosion of safe havens and forest cover dominance.

- Improved intelligence networksthrough community participation.

- Greater administrative reach through roads, BSNL towers, and panchayat engagement.

Remaining Challenges

- Despite progress:

- Bastar regioncontinues to be the core resistance zone due to dense forests and tribal alienation.

- Concerns regarding human rights violationscan undermine trust.

- Inter-state coordinationmust remain strong, especially in border zones.

- Sustainable developmentand rights-based governance remain crucial.

Conclusion

India’s two-decade-long struggle against LWE has finally entered a decisive stage, with significant territorial gains and weakened Maoist leadership. Yet sustainable peace demands not just security operations but deep, inclusive development, protection of tribal rights, and constant strengthening of state capacity in the affected regions.

Editorial 2: Green exception should not become the rule

Context:

The Supreme Court has reopened the debate on legality of post-facto environmental clearances, raising concerns about diluting environmental safeguards.

Introduction

India’s environmental governance is anchored in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) framework, which ensures that development projects undergo scrutiny before execution. Over the years, successive governments have diluted EIA norms, allowing projects to seek ex-post facto (post-facto) clearances. The Supreme Court had previously termed such clearances “illegal”, but the issue has been referred to a larger bench, reopening the debate between development needs and ecological security.

Key Issues Highlighted in the Editorial

- Supreme Court’s Changing Position on Post-Facto Clearances

- In May 2025, a two-judge SC bench struck down the 2017 MoEFCC notification and 2021 OM that legitimized post-facto clearances.

- It held that allowing work to start without prior EC “systematizes violations” of EIA norms.

- On 19 November 2025, a three-judge bench recalledthis judgment and referred the issue to a larger bench, citing concerns that projects worth ₹20,000 crore would otherwise face demolition.

- Justice Ujjal Bhuyan dissented, reiterating: “There is no concept of ex-post facto clearance in environmental law.”

Precautionary Principle & Environmental Jurisprudence

- The precautionary principle is part of Indian environmental law through:

- Vellore Citizens’ Welfare Forum vs Union of India (1996)

- Article 21 (Right to Life)

- Article 48A and 51A(g)

- The principle mandates that environmental harm must be prevented even without full scientific certainty.

- The Court has consistently used this principle to:

- halt destructive mining,

- protect forests and wildlife,

- regulate pollution,

- strengthen environmental clearances.

Why EIA Matters?

- Environmental Impact Assessmentensures:

- scientific evaluation of risks,

- public consultation,

- alternative analysis,

- transparency and accountability.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) identifies EIA as a core preventive toolfor sustainable development.

- The 2017 and 2021 amendmentsweakened this framework by allowing developers to seek clearance after violating norms.

The “Public Interest” Argument and Its Risks

- CJI Gavai emphasized that certain exceptions may be necessary for:

- national security projects,

- essential healthcare services,

- critical connectivity for remote regions.

- However, expanding exceptions can undermine:

- climate adaptation goals,

- environmental rule of law,

- safeguards for indigenous communities,

- India’s commitments under Paris Agreement (2015)and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

- The challenge is to prevent “exceptional” situations from becoming routine shortcuts.

Development vs Environment: SC’s Caution

- The Court has repeatedly urged the government to avoid the simplistic development vs environment binary, noting that:

- long-term ecological damage reduces economic productivity,

- vulnerable communities suffer disproportionately,

- climate change intensifies natural disasters.

- Recent climate-related disasters (heatwaves, floods, landslides) show that ignoring environmental norms has direct livelihood and health consequences.

What the Bench Must Now Re-examine

- The larger bench must consider:

- Whether post-facto clearances violate Articles 21, 48A, 51A(g).

- Whether economic loss can justify environmental violations.

- Whether allowing retrospective approvals incentivises illegal project construction.

- How to reconcile urgent public-interest projects with environmental safeguards.

Conclusion

India’s environmental jurisprudence has consistently emphasized prevention, accountability, and the constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment. While certain exceptions may be justified for genuine public interest, they must remain strictly limited. The Supreme Court’s upcoming decision will significantly shape the future of environmental governance in India—balancing developmental imperatives with ecological integrity.

![]()