09 July 2025 The Hindu Editorial

What to Read in The Hindu Editorial( Topic and Syllabus wise)

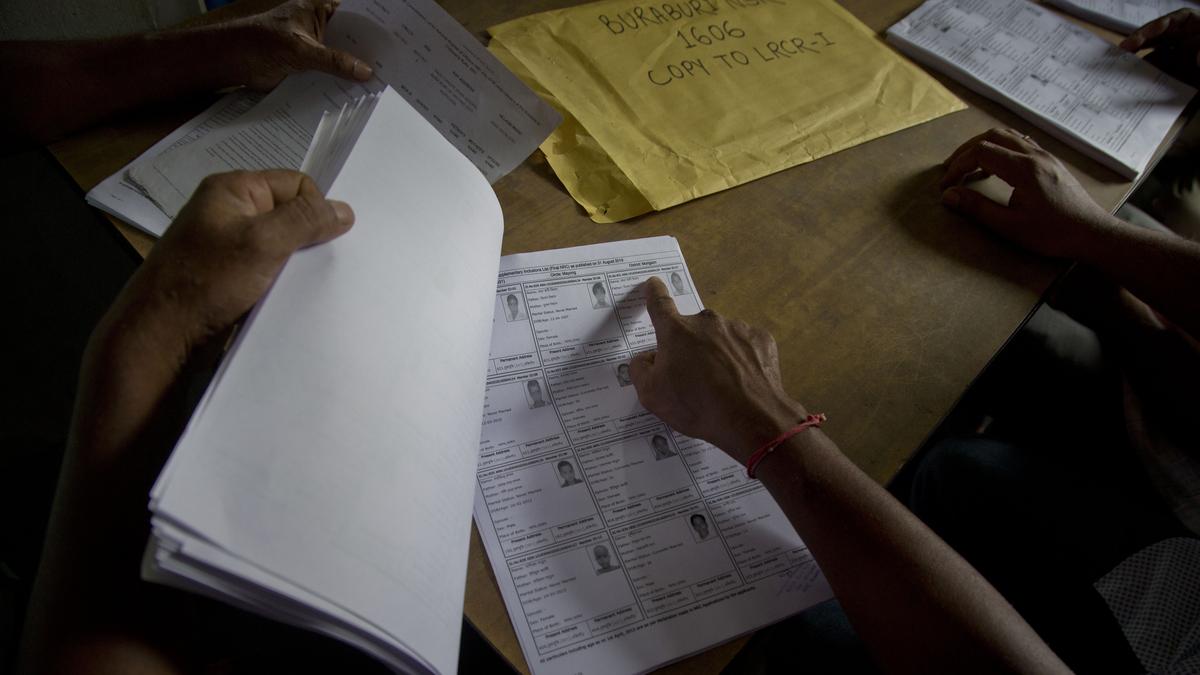

Editorial 1: The dark signs of restricted or selective franchise

Context

A major disruption of India’s electoral democracy is unfolding in Bihar, risking the creation of millions of second-class, insecure citizens.

Introduction

We are now in the second week since the sudden start of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar, which began on June 24, 2025. Many people know this is happening after a gap of over 20 years, but that’s only half the truth. This time, the SIR is very different. It involves a complete rebuilding of the voter list, based on the documents submitted by those who want to register as voters.

Revisiting trauma

- The Special Intensive Revision (SIR)of electoral rolls in Bihar began suddenly on June 24, 2025.

- It has brought back memories of demonetisation (2016)due to its lack of transparency and poor planning.

- People have started calling it ‘votebandi’, comparing it with ‘notebandi’.

- It also resembles the NRC exercise in Assam, which was long, monitored by the Supreme Court, and took 6 years.

Bihar vs Assam: A Comparison

| Aspect | NRC in Assam | SIR in Bihar |

| Duration | 6 years | 1 month |

| Population covered | 33 million applicants | 50 million voters |

| Supervision | Supreme Court | No judicial supervision |

| Exclusions | 2 million people | Potentially large-scale, unclear numbers |

| Documents Required | Varied, with legal aid provisions | 11 rare documents, hard to obtain |

| Timing | Managed and phased | During monsoon and migration peak |

Harsh Documentation Requirements

- The Election Commission of India (ECI)has asked for 11 enabling documents to prove voter eligibility.

- Common documentslike Aadhaar, voter card, ration card, etc., are not accepted.

- Instead, people are asked to provide rare items like:

| Unaccepted Documents | Accepted Documents |

| Aadhaar card | Birth certificate |

| Voter ID | Matriculation certificate |

| Ration card | Land or house ownership record |

| Driving licence | Caste certificate |

| Job card (MGNREGA) | Passport |

- Most common people in Bihardo not possess these rare documents.

Migrant Workers Face the Worst Impact

- High migrationfrom Bihar means many residents live or work outside the State.

- These people may be removed from the voter listif they are seen as not ‘ordinarily residing’ in Bihar.

- During the COVID lockdown in 2020, thousands of Bihari migrants returned home on foot — now, many of them may lose voting rights.

Risk of Mass Disenfranchisement

- Migrants are being labelled as outsiders in their own State.

- Their informal settlementsare being demolished in places like Delhi, and now, they risk being erased from electoral rolls in Bihar.

- The fear of mass disenfranchisementis very real.

- The ECI’s electoral roll in Maharashtrarecently showed a population larger than the actual adult population.

- With no clear explanation for this statistical error, is the ECI now trying to balance the numbersby cutting voters in Bihar?

A fundamental disruption

- The Election Commission of India (ECI)has stated that the Bihar SIR model will be replicated across the country in the coming months.

- This marks a major disruptionin the way electoral democracy has been practised in India since the Constitutionwas adopted and the Representation of the People Act, 1951 was enacted.

- The current ‘votebandi’ exercisein Bihar has created chaos and raised serious concerns about voter rights.

- There are three key warning signalsfor India’s fragile democracy emerging from this exercise.

- The responsibility of proving citizenshipis now being shifted from the State to the individual citizen.

- The empowered voteris now being treated as a suspect, and must prove their eligibility through rare documents.

- This reverses the basic principle of natural justice— where a person is innocent until proven guilty.

- The process converts the default voterinto a doubtful citizen, placing the burden of proof on the poor and document-deficient population.

- If this approach is applied nationwide, it could become a major disasterfor India’s democratic system.

A disenfranchised category

- The Election Commission of India (ECI)says that citizenship is a constitutional requirement for being a voter.

- The current Special Intensive Revision (SIR)is described as merely a verification process to check voter eligibility.

- People whose names were on the 2003 electoral rollare being automatically treated as Indian citizens.

- Everyone elsemust now prove their citizenship through documents, even if they have lived and voted in India before.

- This could lead to the creation of a new class of disenfranchised citizens— people who are legally citizens but are not allowed to vote.

- These individuals would be treated as second-grade citizens, lacking the security and rightsof fully empowered voters.

- Such people would remain dependent on the stateor the majority class to exercise basic rights.

- The impact is alarming— it risks undermining democracy and increasing social divisions.

- Universal adult franchisehas been the foundation of India’s democracy and Constitution.

- In many other countries, marginalised groupshad to struggle for decades to gain equal voting rights — India risks moving backward on that front.

Conclusion

In India, we got the right to vote for everyone at once when we gained freedom and adopted the Constitution. It was not given in parts or slowly. But now, in Bihar, by asking people to submit their educational certificates and property papers, are we moving towards a system where voting rights become limited or selective again?

Editorial 2: Quick fix

Context

Just giving more money in the budget won’t be enough to fix India’s R&D problems.

Introduction

The Union Cabinet’s ₹1-lakh crore RDI scheme marks a major step to boost India’s research ecosystem by involving the private sector in core scientific innovation. Anchored by the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), the initiative aims to shift India’s R&D landscape from government-driven to private-led, hoping to spur long-term technological advancement and global competitiveness.

Overview of the RDI Scheme

- The Union Cabinethas approved a ₹1-lakh crore Research, Development, and Innovation (RDI) scheme.

- It aims to encourage private sector investmentin basic research.

- The scheme includes a special purpose fundhoused within the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF).

- Funds will be provided as low-interest loansto eligible projects.

Role and Structure of ANRF

- ANRF will serve as the custodian of research fundsand be under the oversight of the Science Ministry.

- It is designed as an independent institutional bodyto:

- Allocate research funds to universities and academic institutions.

- Act as a single-window clearance systemfor R&D funding.

- The ANRF is expected to receive about 70% of its funding from private sources.

Government’s Strategic Shift in R&D

- The scheme represents a policy shift—encouraging the private sectorto become the main driver of R&D.

- Currently, the government contributes 70% of India’s R&D spending.

- Through RDI and ANRF, the government wants to reverse this ratio.

Early Concerns and Limitations

- a) Eligibility Restriction: TRL-4

- Only projects that have reached Technology Readiness Level-4 (TRL-4)will qualify for funding.

- TRL is a scale from TRL-1 (basic research)to TRL-9 (fully developed technology), originally designed by NASA.

- Supporting only TRL-4 projects excludes early-stage or high-risk innovations.

- This creates a bias towards safer, mid-stage projects, potentially undermining disruptive innovations.

- b) Lack of Risk Appetite

- The scheme lacks the risk-taking spiritneeded to fund long-term or uncertain innovations.

- In contrast, countries like the U.S. have built technologies (e.g., Internet, GPS) through military-industrial R&D.

Structural Challenges in India’s Innovation Ecosystem

- Brain drain continuesas Indian scientists migrate abroad due to better opportunities.

- India lacks a deep-skilled manufacturing baseto convert research into scalable products.

- Budgetary support alone cannot resolvestructural problems; it requires long-term institutional reforms.

Conclusion

While the RDI scheme and ANRF reflect bold intent, challenges remain—especially in risk appetite, manufacturing capacity, and retaining scientific talent. For India to become a global R&D leader, the ecosystem must support early-stage innovation, tolerate failure, and build strong research-industry linkages. Success will depend on sustained reforms, not just funding injections or selective eligibility filters.

![]()